https://dronebotworkshop.com/dc-gearmotors-pwm/

Control Large DC Gearmotors with PWM & Arduino | DroneBot Workshop

Pulse Width Modulation, or PWM, is an excellent method of controlling DC motors, however controlling large gearmotors can be expensive and difficult – but it doesn't have to be. Today I will introduce…

dronebotworkshop.com

Introduction

I’m very excited to announce a new project here in the workshop!

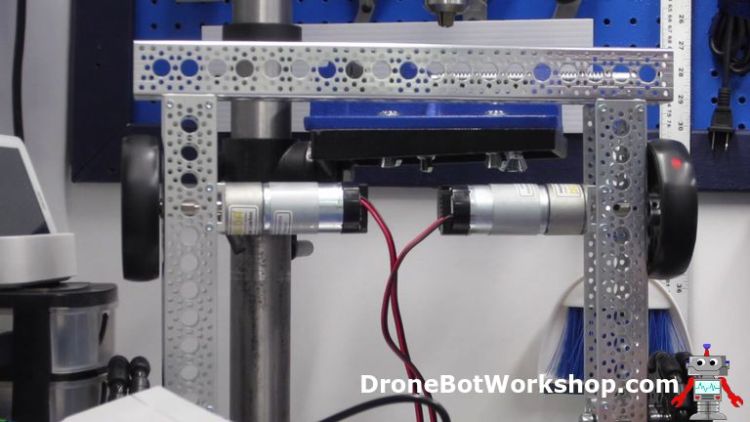

I’m building a robot. This probably won’t come as Earth-shattering news on a site called “DroneBot Workshop”, but this robot is different. Unlike the small “robot car” bases I’ve used in past projects, this will be a big robot. A capable robot.

A “real” robot!

Real robots need big motors and for my robot, I’ve chosen a couple of large DC gearmotors to do the job. These powerful motors consume a lot of current, which means I’ll need to use a motor driver that can handle the current without burning up.

Today I’ll show you how to do exactly that, control a large DC gearmotor and change its speed and direction. I’ll be using an Arduino to create a Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) signal to regulate the motor speed and a Cytron MD10C motor driver to supply the power.

Let’s get started!

DC Gearmotors

DC gearmotors are used in many electromechanical applications in appliances, industry, and robotics. Their high torque and low cost make them popular components for experimenters and hobbyists.

A “normal “DC motor spins at a very high speed, often several thousand RPM. This is great for a high-speed drill but much too fast for spinning wheels to move a robot or car around.

In a gearmotor there are, not surprisingly, a set of gears that reduce the motor speed to something more manageable, a few hundred RPM or even less. The motor I’m using has a full-speed shaft rotation of just 110 RPM.

When you reduce speed using gears you also increase torque, this inverse relationship means the slower you gear the motor down the more torque it will have.

Most DC gearmotors, including the one I purchased for my robot, use brushed DC motors.

Pulse Width Modulation

Pulse Width Modulation, or PWM, is a method of controlling the speed of a motor. It actually has many uses beyond that, controlling lights and LED’s and data communications are a few other applications of PWM.

With PWM control the DC current applied to the motor is sent in square-wave pulses. The width of the pulses is changed to regulate motor speed, the wider the pulse the faster the motor will spin.

The pulse width is expressed as a percentage, at 50% the output is a perfect square wave. At 75% the pulse spends 75% of its time HIGH, the rest LOW. At 25% it is HIGH 25% of the time and LOW for 75%.

This width is called the “duty cycle”.

At 100% width the pulse is constantly HIGH. The motor receives full power and spins at its rated output speed.

At 0% the signal is constantly LOW, essentially meaning no voltage at all. Obviously, this causes the motor to stop.

For a detailed explanation of PWM please see the article “Controlling DC Motors with the L298N Dual H-Bridge and an Arduino”.

H-Bridges

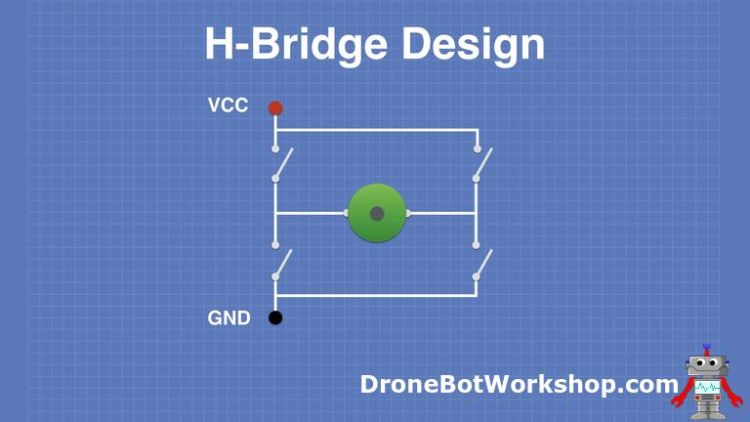

A common method of controlling a DC motor is to use an “H-Bridge”. This type of controller allows you to change the polarity of the current sent to the motor.

H-Bridge Operation

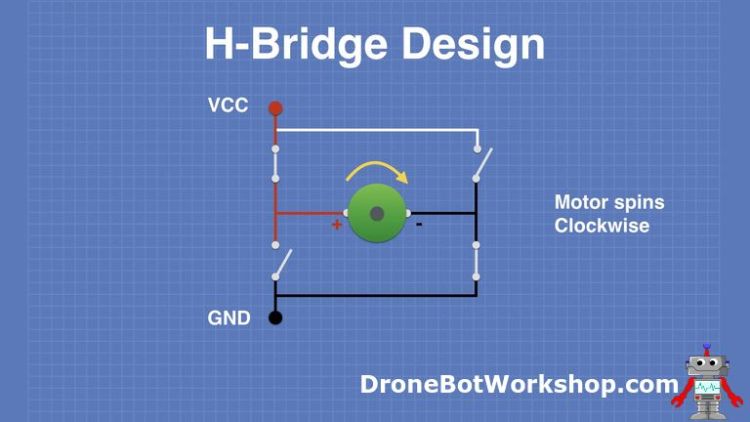

An H-Bridge is an arrangement of switches that allows you to apply current to a DC motor and reverse the polarity to spin the motor in the opposite direction, as illustrated below:

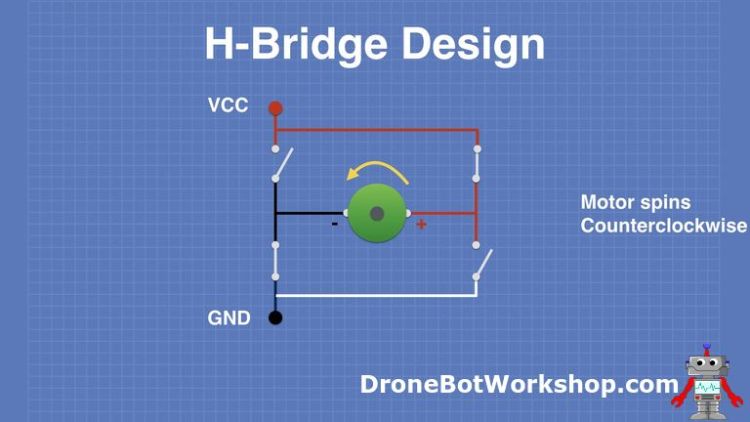

By turning on two of the switches the current is directed to the motor, In the following illustration, the motor spins clockwise when the switches are turned on:

Turning those switches off and then turning on the remaining two switches will cause the polarity of the current to be reversed. As a result, the motor spins counterclockwise.

Of course in real life, we seldom would use switches to create an H-Bridge.

Instead, we would use an active semiconductor switch, like a transistor, to do the switching for us.

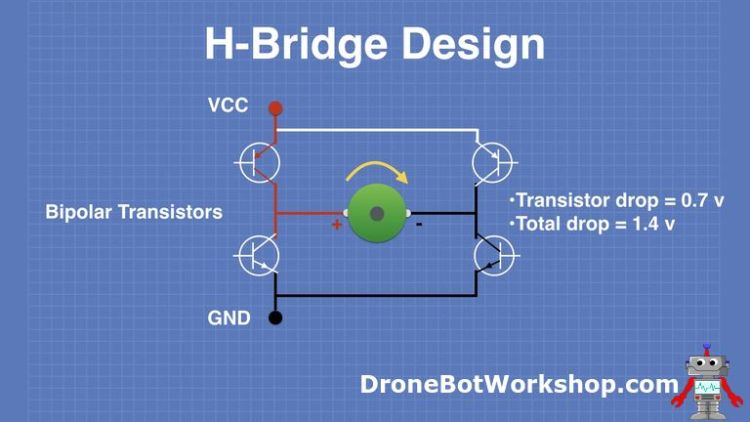

H-Bridge with Bipolar Transistors

In a traditional H-Bridge, like the L298N, the switching elements are built with bipolar transistors.

Bipolar transistors are the oldest and one of the most common types of transistor. They are inexpensive and readily available, making them ideal for use in circuits like H-Bridges.

The problem with bipolar transistors is that in switching mode they act a lot like a “switched diode”, and like any diode, they have a voltage drop. A voltage drop of 0.7 volts.

While that may not sound like a lot of voltage it actually does cause a lot of issues with H-Bridge circuits based upon bipolar transistors.

First, there are two transistors, so the total voltage drop is 1.4 volts. This is significant, especially for low-voltage motors like the 6-volt ones commonly used in small robot cars. A 6-volt power supply would only deliver 4.6 volts (6 – 1.4) to the motor, causing it to operate below its peak efficiency.

Second, that voltage doesn’t just disappear. Instead, it is dissipated, mostly as heat. This is why many H-Bridge designs require big heatsinks.

There is actually a better component that can be used, one that doesn’t exhibit the problems suffered by bipolar transistor designs.

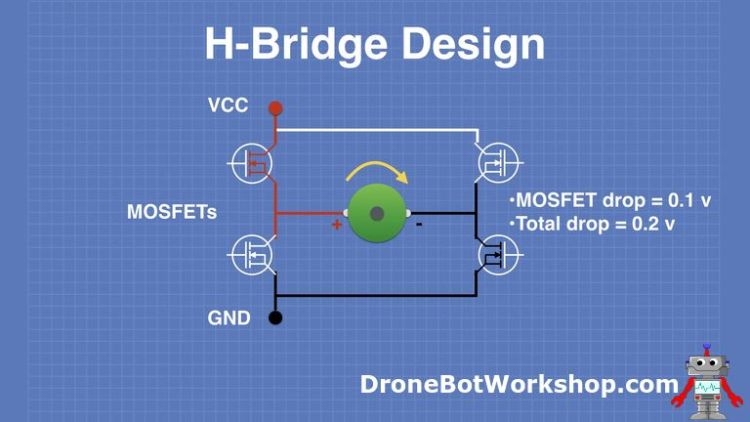

H-Bridge with MOSFETs

A metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor, or MOSFET, is a more advanced transistor that has become extremely popular in switching and amplifier circuits.

When used as switch a MOSFET acts more like a “switched resistor” than a “switched diode”. A very low-value resistor at that.

This gives the MOSFET a very low voltage drop. The 0.1-volt drop on the above illustration is actually just an estimate, as a MOSFET acts more like a resistor the actual voltage drop is really determined by the amount of current flowing through it.

Suffice to say that the voltage drop is extremely low.

Because the MOSFET doesn’t drop the voltage as much as a bipolar transistor it is superior to the bipolar transistor in the following ways:

- It loses a lot less voltage, practically none at all. This makes it ideal for low-voltage applications.

- Because of the low voltage drop, it produces far less heat. Most of the energy is used to power the motor, very little is lost in the H-Bridge.

For the large gearmotor I’m working with I’ll be using a motor driver based upon MOSFETs.

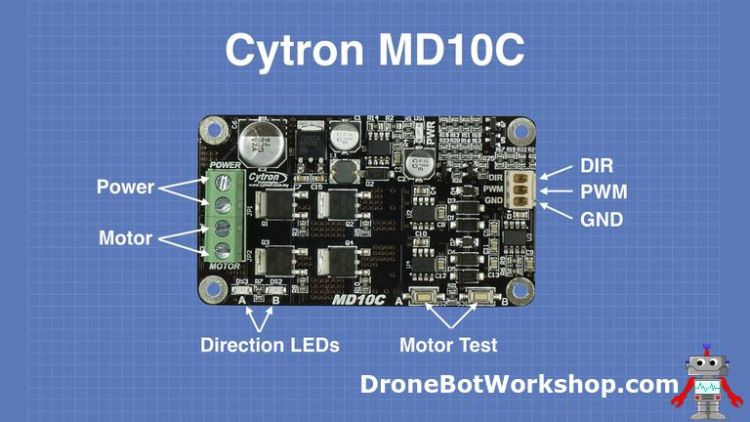

Cytron MD10C Motor Driver

When searching for a MOSFET-based H-Bridge that could power my motor I ran across several devices. Most of them were fairly expensive, often exceeding the cost of the motor itself.

There are, however, a few exceptions.

One of them is the Cytron MD10C driver board. It’s inexpensive and has some very impressive features.

Cytron MD10C Specifications

The Cytron MD10C is a MOSFET-based motor driver that is very easy to use. It has the following specifications:

- Power supply – 5 to 30 volts DC. This is the power supply for the motor, the MD10C has an internal voltage regulator to supply its own logic circuits.

- Maximum continuous motor current of 13 amperes.

- Peak motor current of 30 amperes. This can be sustained for up to 10 seconds.

- It works with both 3.3-volt and 5-volt logic systems.

- It has a maximum PWM frequency of 20 KHz. You’ll see in a few moments how important that is.

- It has two push buttons to test your motor connections and two LEDs to indicate motor direction.

Another feature, of course, is its low price. It’s currently available for less than 12 US dollars per unit, much less than drivers with similar specifications.

Cytron MD10C Connections

Hooking up the Cytron MD10C is very simple.

On one side of the board there are four screw terminals, they are as follows:

- Power + – The 5 to 30-volt power supply Positive input.

- Power – – The 5 to 30-volt power supply Negative or Ground input.

- Motor A – One side of the motor coil.

- Motor B – The other side of the motor coil.

On the opposite end of the board you will find the input connector. It has three pins, as follows:

- DIR – This is the Direction input, a logic-level signal that determines which direction the motor shaft will spin.

- PWM – The Pulse Width Modulation signal input. This regulates the motor speed.

- GND – A Ground connection.

There are also two push buttons on the board, labeled “A” and “B”. Pressing either one of these will spin the motor in one or the other direction, depending upon which one you press. It is a nice feature as it allows you to test your motor and power supply wiring without needing a PWM controller.

The motor direction is also indicated by two LEDs, also labeled “A” and “B”.

Cytron MD10C vs L298N H-Bridge

The Cytron MD10C has several advantages over the L298N.

- It can handle 13 amperes continuous, versus the 3 amperes that the L298N can handle.

- It is much more efficient due to the use of MOSFETs. The MD10C has a very low voltage drop, meaning that most of the energy is sent to the motor coils. The L298N, on the other hand, drops 1.4 volts.

- Because of its efficiency, the Cytron MD10C does not require a heatsink. The L298N needs a good-sided heatsink to dissipate the energy absorbed by its bipolar transistors.

The high-efficiency and low heat dissipation make the Cytron MD10C ideal for robotics applications, where every bit of energy needs to be used as efficiently as possible.

Physically the L298N board is about half the size as the MD10C, and you should also note that the L298N can drive two motors whereas the MD10C is a single motor controller.

Cytron also manufactures the MD10A, a dual-channel version of the MD10C.

The board is packaged along with some plastic standoffs and a connector for the input, a nice touch.

Arduino PWM

We have used Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) with the Arduino in many of our designs, for DC and servo motor control as well as for regulating the intensity of LEDs.

In the Arduino IDE you can control PWM using the analogWrite command. This command has two inputs:

- The pin that you are sending the PWM out of.

- The PWM value, from 0 to 255. A value of 0 indicates no speed (output held LOW) and 255 is full-speed (output held HIGH).

Not every pin on the Arduino is capable of PWM. On many Arduino (and clone) boards you’ll notice a small symbol beside the PWM-capable pins, usually a sine or square wave or tilde sign (i.e. “~” ).

On the Arduino Uno pins 3, 5, 6, 9, 10, and 11 support pulse width modulation.

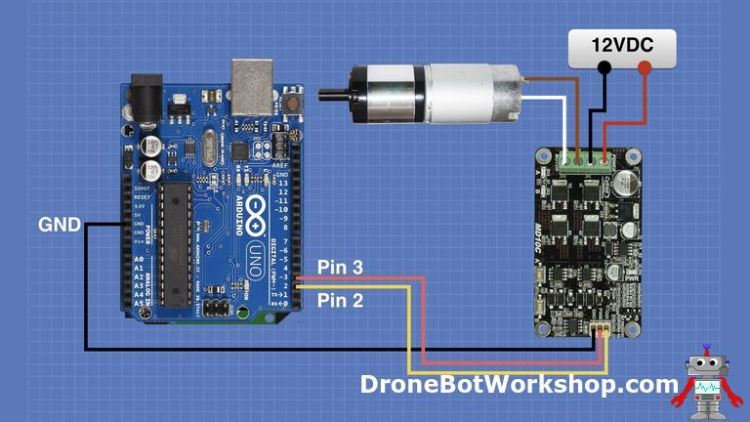

Arduino Hookup

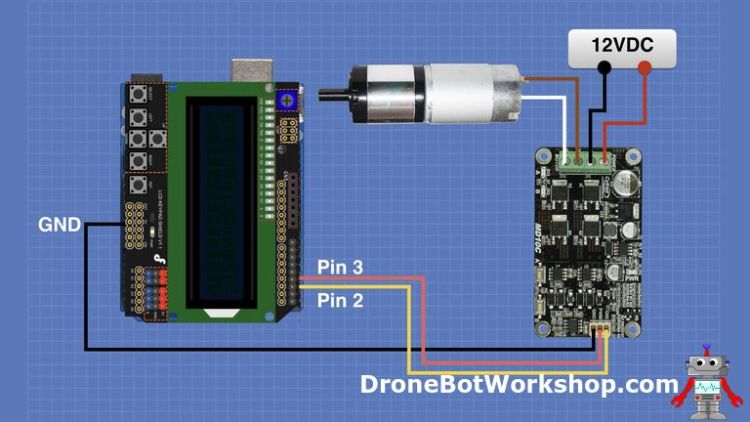

In our Arduino PWM controller we are going to make use of another component that I’ve worked with before, the LCD Keypad Shield. You’ll find details for using this shield in the article Using LCD Displays with Arduino.

The keypad shield has a number of push buttons and they operate in a rather unique fashion. Instead of using digital I/O pins these buttons are connected to a resistor array. The array acts as a voltage divider and every time you press a button you’ll send a different voltage out. This is read on analog input A2 on the Arduino.

Hooking up all the components for our PWM test is pretty simple.

You’ll need to supply power that is suitable for your motor, I show a 12-volt power supply here but if you have a motor with a different voltage rating then you should change this to suit your motor. Keep in mind that the MD10C has a voltage range of 5 to 30-volts.

Make sure that your power supply has a suitable current rating for powering your motor.

There are not many connections to the Arduino at all, just the ground and the DIR and PWM pins. I’m using pin 3 as it is PWM-capable.

After you get it all wired up install your keypad shield.

In my test setup, I used an additional shield, a prototyping shield with screw terminals. This is a really handy shield as it sits in between the Arduino Uno (or Mega) and the shield you are working with. Screw terminals are provided for access to every Arduino pin.

This arrangement allows me to connect to the Arduino while a shield is mounted, otherwise, you may need to do a bit of soldering to make the connections.

Basic Arduino PWM Sketch

Cytron provides an Arduino sketch that can be obtained through the MD10C Wiki, unfortunately the sketch is not really usable in the form they provide it. Two problems actually:

- It uses pin 2 as a PWM output, but pin 2 is not PWM-capable.

- It uses a library for the LCD Keypad that is not very easy to find.

I’ve resolved both those issues and fixed up a bit of the code. Here is what it looks like now:

/*

PWM Motor Test

pwm_motortest.ino

Uses LCD Keypad module

Modified from Cytron example code

DroneBot Workshop 2019

https://dronebotworkshop.com

*/

// Include libraries for LCD Display

#include <LiquidCrystal.h>

#include <LCD_Key.h>

// Define keycodes

#define None 0

#define Select 1

#define Left 2

#define Up 3

#define Down 4

#define Right 5

// Pin for analog keypad

#define diy_pwm A2

// PWM output pin

#define pwm 3

// Motor direction pin

#define dir 2

// Define LCD display connections

LiquidCrystal lcd(8, 9, 4, 5, 6, 7);

// Setup LCD Keypad object

LCD_Key keypad;

// Variable to represent PWM value

int pwm_value = 0;

// Variable to represent Keypad value

int localKey;

void setup(){

// Setup LCD

lcd.begin(16, 2);

lcd.clear();

// Define Pins

pinMode(pwm,OUTPUT);

pinMode(dir,OUTPUT);

}

void loop()

{

while(1)

{

// Scan keypad to determine which button was pressed

localKey = keypad.getKey();

// Toggle motor direction if LEFT button pressed

if(localKey==Left){

digitalWrite(dir,!digitalRead(dir));

delay(200);}

// Increase motor speed if UP button pressed

if(localKey==Up){

pwm_value++;

delay(200);

lcd.clear();}

// Decrease motor speed if DOWN button pressed

else if(localKey==Down){

pwm_value--;

delay(200);

lcd.clear();}

// Ensure PWM value ranges from 0 to 255

if(pwm_value>255)

pwm_value= 255;

else if(pwm_value<0)

pwm_value= 0;

// Send PWM to output pin

analogWrite(pwm,pwm_value);

// Display results on LCD

lcd.setCursor(0,0);

lcd.print("PWM:");

lcd.print(pwm_value);

lcd.setCursor(0,1);

lcd.print("DIR:");

lcd.print(digitalRead(dir));

}

}

You can get the LCD Keypad library, as well as all of the sketches used in this article, from the link in the resources section at the bottom of this article.

The sketch starts by including both the LCD Keypad library and the LiquidCrystal library. The latter is included in your Arduino IDE.

Next the keycodes are defined for the keys on the LCD keypad.

We then define the analog A2 pin to be the pin the keypad is connected to . We also define two output pins for the PWM and DIR connections.

Next we setup objects for both the LCD display and the keypad itself. Note the pins used to connect the LCD are defined here.

Finally, we define a couple of variables – one to represent the PWM value (from 0 to 255) and the other to represent the keypad button value. The PWM value is also initialized at zero, so that the motor will be stopped when the Arduino is powered on or reset.

In the Setup section we set up the LCD display as a 16 character, 2-line display. We also define the PWM and DIR pins to be outputs.

Now onto the loop!

The loop starts with a “while(1)” statement. This statement simply means that the code within the while statement is executed infinitely.

In the while(1) statement we first get the keypad value. We then perform an action depending upon what key is pressed.

- If the LEFT button is pressed then we toggle the DIR pin to change motor direction.

- If the UP button is pressed we increment the PWM speed value by 1.

- If the DOWN button is pressed then we decrement the PWM speed value by 1.

The RIGHT button is undefined. The Reset button is connected to the Arduino Reset line and will (what else?) reset the Arduino when pressed. This is also a good way to instantly stop the motor as we initialized the PWM speed value as zero.

We then check the PWM value to ensure that it stays in the range of 0 to 255.

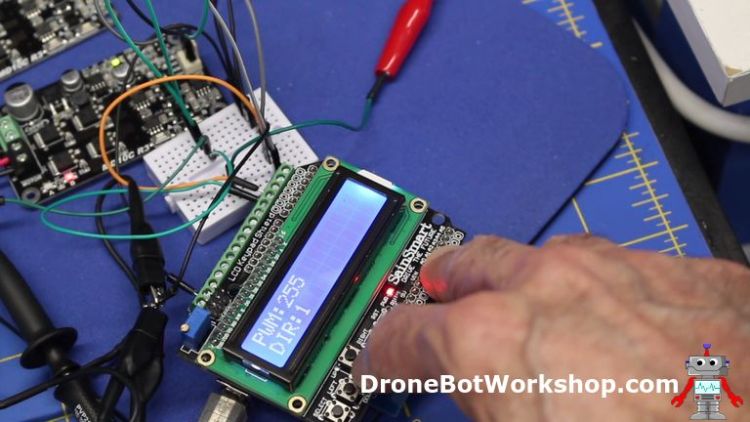

Finally, we write the PWM and DIR values to the LCD display.

Load the sketch to your Arduino and give it a try. You should be able to control the speed of your motor using the UP and DOWN buttons and change its direction with the LEFT button.

When I tested it everything seemed to work properly. However, it isn’t perfect.

Arduino PWM Results

The controller had no problem changing the speed and direction of my motor. At the lower speeds, however, it caused the motors to emit a loud “whining” sound.

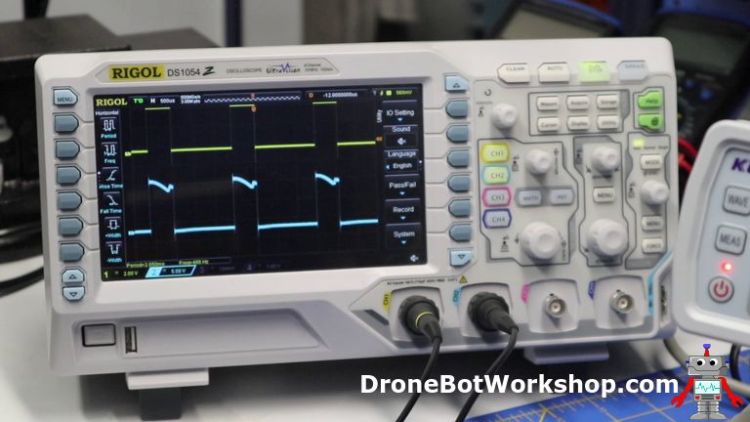

When I hooked an oscilloscope to the motor leads I observed that the signal was very distorted, indicating that the transfer of energy was not 100% efficient. I also observed that the motor was consuming a lot of current, especially at higher speeds.

Our PWM controller may be able to be improved. Let’s see what we can do to make it better.

PWM Frequency

I measured the PWM frequency that came from our Arduino controller and got a value of 488 Hz. This is obviously the source of the “whining” sound, and it also is the reason that the waveform is so distorted.

The motor coil(s) are acting like inductors and so the output of the MD10C is really part of a tuned circuit. And it looks like our circuit is out of tune!

Changing the PWM frequency could resolve this. In fact, some industrial PWM controllers use frequencies above the range of human hearing to control their motors.

Raising the PWM Frequency

Raising the PWM frequency has a lot of advantages, but like any good thing it’s possible to overdo it.

There is sort of a “sweet spot” for PWM frequency. As the frequency rises the torque of the motor can be reduced. Initially this reduction is minimal, however once you go above a certain frequency it falls rapidly.

The frequency just before this point is the ”sweet spot”. A place where the frequency is high enough to prevent “whining” and yet still allows the motor to produce full, or nearly full, torque.

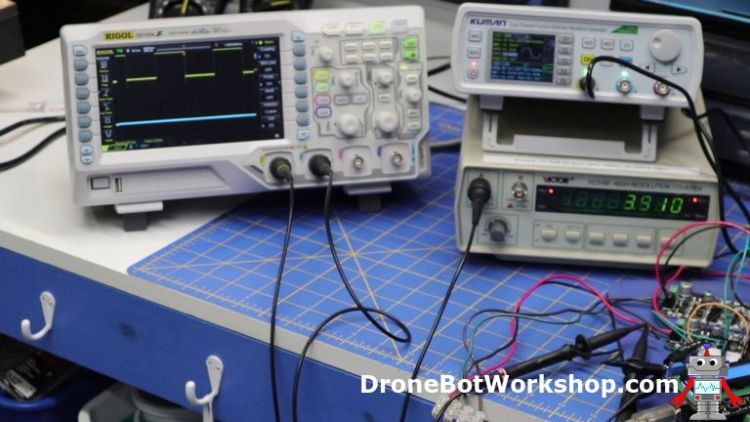

To determine my motors “sweet spot” I disconnected the Arduino PWM output and instead used the output of a signal generator, set to deliver a 5-volt square wave.

With the signal generator I could adjust both the frequency and the duty-cycle of the square wave, the duty-cycle gives me control over the motor speed.

As I increased the frequency I observed the waveform on the oscilloscope, as well as the sound emitted by the motors.

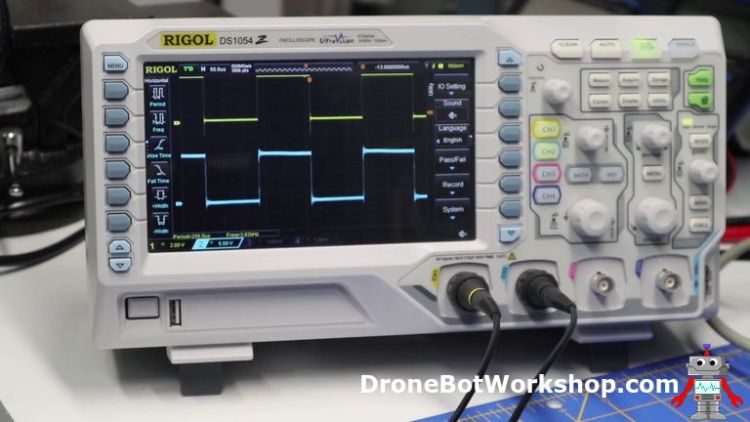

<INSERT IMPROVED WAVEFORM>

By the way, the top trace (which is the input signal) may look a bit rounded but in reality, it isn’t, it’s a result of being loaded down by the probe to my frequency counter!

The real business is the bottom trace, the blue pone. Note how much nicer ot looks than the original trace that I saw when examining the Arduino PWM.

Clearly raising the PWM Frequency would be a good thing to do, assuming of course that it doesn’t reduce the torque of my motors by any noticable amount.

Motor Torque Test

I decided to give my motors a “real world” test as I don’t have access to equipment that can measure the torque value.

For my test, I placed a 10 Kg (22 lb) bag of road salt onto the test platform. For those of you unfamiliar with road salt we use it in winter climates to melt ice and provide traction. Today I’m using it to test some motors!

I placed the bag of salt onto the platform, on top of a board that itself probably adds an additional pound of weight to the platform. I set the PWM frequency to 3 KHz and the duty cycle to 50% (half speed).

The platform had no problem moving around and the total current draw was less than the unloaded current I observed when testing the original Arduino sketch.

Obviously increasing the frequency of my PWM signal is something I’ll want to do when I build my new robot.

Changing Arduino PWM Frequency

The PWM frequency that the Arduino used was 488 Hz, at least on pin 3. Turns out that had I used a different pin I could have doubled that, they are not all the same. But that still would be only 976 Hz, an improvement but not exactly what I want.

At a glance that seems to be about the best I could do, the Arduino doesn’t seem to have a method of altering its PWM frequency. Or does it?

Turns out that you CAN alter the frequency after all. To do so requires you to understand how that frequency is established in the first place, and that brings us to the subject of the Arduino registers and timers.

Arduino Registers and Timers

Pulse width modulation is generated in the Arduino using some internal registers in the ATmega328 chip that powers the Arduino board.

The ATmega328 chip has three PWM timers, controlling 6 PWM outputs. By manually manipulating the chip’s timer registers you can change the PWM frequency.

For a detailed explanation of this an excellent source is the Secrets of Arduino PWM article on the Arduino website.

One thing that you need to be aware of. Modifying the internal timer registers will affect several other Arduino functions, including delay, tone and servo. So be careful if yo ualso wish to use those functions in your code.

Arduino PWM High-Frequency Sketch

I found some code that originated on the Arduino forum and that was authored by a user named “macegr”. I took that function and integrated it into the code we used earlier.

/*

PWM Motor Test - High Frequency

pwm_motortest_hi.ino

Uses LCD Keypad module

Runs at higher PWM frequency

Modified from Cytron example code

setPwmFrequency from macegr of the Arduino forum

DroneBot Workshop 2019

https://dronebotworkshop.com

*/

// Include libraries for LCD Display

#include <LiquidCrystal.h>

#include <LCD_Key.h>

// Define keycodes

#define None 0

#define Select 1

#define Left 2

#define Up 3

#define Down 4

#define Right 5

// Pin for analog keypad

#define diy_pwm A2

// PWM output pin

#define pwm 3

// Motor direction pin

#define dir 2

// Define LCD display connections

LiquidCrystal lcd(8, 9, 4, 5, 6, 7);

// Setup LCD Keypad object

LCD_Key keypad;

// Variable to represent PWM value

int pwm_value = 0;

// Variable to represent Keypad value

int localKey;

void setup(){

// Setup LCD

lcd.begin(16, 2);

lcd.clear();

// Set the PWM Frequency

setPwmFrequency(pwm, 8);

// Define Pins

pinMode(pwm,OUTPUT);

pinMode(dir,OUTPUT);

}

void loop()

{

while(1)

{

// Scan keypad to determine which button was pressed

localKey = keypad.getKey();

// Toggle motor direction if LEFT button pressed

if(localKey==Left){

digitalWrite(dir,!digitalRead(dir));

delay(200);}

// Increase motor speed if UP button pressed

if(localKey==Up){

pwm_value++;

delay(200);

lcd.clear();}

// Decrease motor speed if DOWN button pressed

else if(localKey==Down){

pwm_value--;

delay(200);

lcd.clear();}

// Ensure PWM value ranges from 0 to 255

if(pwm_value>255)

pwm_value= 255;

else if(pwm_value<0)

pwm_value= 0;

// Send PWM to output pin

analogWrite(pwm,pwm_value);

// Display results on LCD

lcd.setCursor(0,0);

lcd.print("PWM:");

lcd.print(pwm_value);

lcd.setCursor(0,1);

lcd.print("DIR:");

lcd.print(digitalRead(dir));

}

}

void setPwmFrequency(int pin, int divisor) {

byte mode;

if(pin == 5 || pin == 6 || pin == 9 || pin == 10) {

switch(divisor) {

case 1: mode = 0x01; break;

case 8: mode = 0x02; break;

case 64: mode = 0x03; break;

case 256: mode = 0x04; break;

case 1024: mode = 0x05; break;

default: return;

}

if(pin == 5 || pin == 6) {

TCCR0B = TCCR0B & 0b11111000 | mode;

} else {

TCCR1B = TCCR1B & 0b11111000 | mode;

}

} else if(pin == 3 || pin == 11) {

switch(divisor) {

case 1: mode = 0x01; break;

case 8: mode = 0x02; break;

case 32: mode = 0x03; break;

case 64: mode = 0x04; break;

case 128: mode = 0x05; break;

case 256: mode = 0x06; break;

case 1024: mode = 0x07; break;

default: return;

}

TCCR2B = TCCR2B & 0b11111000 | mode;

}

}

The sketch is basically identical to the last one with the addition of a function called setPwmFrequency. This function takes two inputs:

- The PWM pin on the Arduino

- The divisor, the amount you want to divide the master frequency by.

In the Setup I added a call to this function, otherwise, nothing else has changed.

After changing the sketch I loaded it up to the Arduino and repeated the test. This time the frequency I obtained was 3909 Hz or 3.909 KHz!

Observing the waveform on the oscilloscope I was pleased to see that it looked almost perfect. And the “real world” test with the big bag of salt worked well, the platform had no problem moving the load around even at very low speeds.

And finally, the current draw from the power supply was very low, the lowest readings I received in all my tests.

When I build my final motor controller for my robot I will definitely be using this method!

Conclusion

Controlling large DC motors with pulse width modulation isn’t so hard, as long as you have the right driver and controller. The Cytron MD10C is an excellent choice for motor driver and by altering the Arduino PWM frequency we can build an efficient controller to go along with it.

I hope you enjoyed this article and found it beneficial. Please look out for my new series, Build a REAL Robot, coming up very soon!

Resources

Code and Library – The Two sketches and the LCD Library, all in one handy ZIP file!

Cytron MD10C Users Manual – The guide for the Cytron MD10C motor driver.

'사물인터넷' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Experiments with the RCWL-0516 – Doppler Radar Distance Sensor (0) | 2021.07.04 |

|---|---|

| Using OLED Displays with (0) | 2021.07.04 |

| SD Card Experiments with Arduino (0) | 2021.07.04 |

| Using a Real Time Clock with Arduino (0) | 2021.07.04 |

| Using Rotary Encoders with Arduino (0) | 2021.07.04 |