https://dronebotworkshop.com/eeprom-arduino/

EEPROM with Arduino - Internal & External

Learn how to use both internal and external EEPROM (Electrically Erasable Read-Only Memory) to provide nonvolatile storage for your Arduino projects.

dronebotworkshop.com

Today we will be working with EEPROMs, a special type of memory chip that keeps its data even after powering down your project.

Introduction

Computers and microcontrollers need memory to store data, either permanently or temporarily, and while this memory can come in a variety of forms it can be divided into two basic types – volatile and nonvolatile.

Volatile memory is usually in the form of RAM or Random Access Memory. This is the “working” memory for your device, it holds temporary data used during program operation. Once the power is removed the memory is erased.

Nonvolatile memory, as you may have guessed by now, retains its data even after being powered-down. There are a variety of different types of non-volatile memory, and today we will be examining one of them – the Electrically Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory or EEPROM.

Specifically, we will be looking at how to use EEPROM with an Arduino.

Understanding EEPROMs

There are many other forms of non-volatile memory, including Flash memory, SD Cards, USB drives, hard disk drives, and SSDs. So where does the EEPROM fit in all of this?

Compared to the aforementioned memory types an EEPROM has a very small amount of storage, in fact, EEPROM capacities are commonly measured in Bits as opposed to Bytes. Since they only store a small amount of data they don’t consume a great deal of current, making them ideal for battery and low-powered applications.

EEPROMs were developed in the early 1970s and the first EEPROM was patented by NEC in 1975.

Non-Volatile Memory Types

An EEPROM is constructed using an array of floating-gate transistors, with two transistors per bit. It is part of the ROM, or Read-Only Memory, family of devices.

EEPROMs are similar to Flash Memory, the difference being that Flash Memory is larger and uses larger data blocks. This comes at the expense of the number or rewrites or “write cycles”, Flash Memory can only be rewritten about 10,000 times.

The Arduino microcontrollers use Flash Memory to store the programs (sketches) that are uploaded to it. Arduino also has internal EEPROM, as we will see shortly.

Other members of the ROM family include the following:

- ROM – Read-Only Memory. These chips are programmed during manufacture and cannot be altered.

- PROM – Programmable Read-Only Memory. These chips can be programmed using a special device, however, they can not be erased and reprogrammed.

- EPROM – Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory. Like a PROM, an EPROM requires a special programming device. This type of memory chip can be erased using ultraviolet light and then reused.

As it requires no external programming or “burning” device an EEPROM is the easiest of these devices to use.

EEPROM Limitations

With all of their wonderful features, there are also some limitations that need to be considered when using an EEPROM in your design.

As with Flash Memory, EEPROMs have a limited number of write cycles. You can read from them as much as you want, but you can only write or rewrite the data a given number of times.

The limit on write cycles for common EEPROMs is from about 100,000 to 2 million write cycles.

A few hundred thousand or even a couple of million write cycles may sound like a lot, but consider how fast a modern microcontroller or microprocessor can write data and you’ll soon realize that it can become a severe limitation. If you were to rewrite to the EEPROM every second and it has a write cycle capacity of 100,000 writes then you’d exceed that capacity in a little over one day!

When designing using EEPROMs you will want to write to the device as little as possible. Another technique, which we will examine in a while, is to read the bit first before it is written – no sense rewriting it if it is already the correct value.

Another EEPROM limitation is data retention time. While EEPROM technology is constantly improving todays EEPROMs can retain data for about 10 years at room temperature before it becomes corrupted. Rewriting that data will start the counter again, prolonging the life of the EEPROM.

And finally, an obvious limitation of sorts is the EEPROM storage capacity, which is quite small when compared to other memory devices. But, as the most common use of EEPROMs is to retain configuration and calibration data, this is seldom an issue.

EEPROM with Arduino – Two Types

Adding EEPROM to our Arduino designs can allow our projects to retain data after being powered down. This can be very useful for applications that require calibration, or the storage of a user’s favorite settings.

Internal EEPROM

We can add EEPROM capability to our Arduino projects quite easily. In fact, the Arduino already has some internal EEPROM that we can use in our programs. The amount of memory depends upon which Arduino model we are using.

The following table illustrates the amount of internal EEPROM in some popular Arduino models:

| Microcontroller | EEPROM Capacity |

| Atmega2560 (Arduino Mega 2560) | 4096 Bytes |

| ATmega328 (Arduino Uno, Mini ands some Nanos) | 1024 Bytes |

| ATmega168 (Some Nanos) | 512 Bytes |

In many designs, this small amount of non-volatile memory will be sufficient.

External EEPROM

If your design requires more EEPROM capacity then you can add an external EEPROM.

As EEPROMs operate on a bit level they are usually designed to use serial data, in other words, data that is transmitted one bit at a time. This has lead to the development of many I2C-based EEPROM devices.

Using an I2C EEPROM device with an Arduino is very simple, as the Arduino already has connections for I2C and libraries to use them. Many of the I2C EEPROMs can be configured for unique addresses, allowing you to use multiple devices in the same circuit.

Another advantage with many I2C EEPROMs is that they have a larger write-cycle tolerance than the 100,000 writes you are limited to with the Arduino internal EEPROM.

Using Internal EEPROM

We will start our EEPROM experiments using the internal EEPROM in the Arduino. For our experiment I’m using an Arduino Uno, but you may substitute a different Arduino if you prefer.

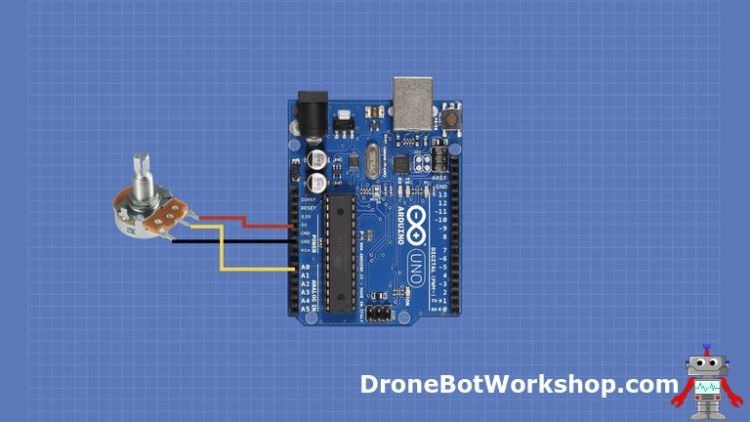

In order to demonstrate the internal EEPROM, we will add a potentiometer to our Arduino, connecting it to one of the analog input ports. Here is the hookup:

After you get it hooked up, connect the Arduino to your computer running the Arduino IDE.

Arduino EEPROM Library

Our experiments will be greatly simplified by using the Arduino EEPROM Library, which is already included in the Arduino IDE.

The library comes with a number of short example sketches. We can use them to experiment with the Arduino’s internal EEPROM. Note that the library only works with the internal EEPROM, to use an external device will require a different library.

In order to use the example programs in the Arduino IDE go through the following steps:

- Start the Arduino IDE.

- Click on the File menu on the top of the screen.

- Select Examples. A sub-menu will appear.

- Select EEPROM. An additional sub-menu will appear.

- You may select an example from the sub-menu.

There are eight examples included with the library, and the code within them will assist you in writing your own code for working with the Arduino built-in EEPROM. Here are a few you can try:

EEPROM Update

Although there is an EEPROM Write sketch, using the update method is a better choice when writing data to the EEPROM. This is because this method reads the EEPROM value first, and then only updates it if it is different, in fact it’s simply a combination of both the Read and Write method.

By doing this the number of writes to the EEPROM are reduced, and considering that the Arduino EEPROM has a write cycle life of 100,000 operations that is a good thing to do.

This technique is often referred to as “wear levelling”.

EEPROM Update

/***

EEPROM Update method

Stores values read from analog input 0 into the EEPROM.

These values will stay in the EEPROM when the board is

turned off and may be retrieved later by another sketch.

If a value has not changed in the EEPROM, it is not overwritten

which would reduce the life span of the EEPROM unnecessarily.

Released using MIT licence.

***/

#include <EEPROM.h>

/** the current address in the EEPROM (i.e. which byte we're going to write to next) **/

int address = 0;

void setup() {

/** EMpty setup **/

}

void loop() {

/***

need to divide by 4 because analog inputs range from

0 to 1023 and each byte of the EEPROM can only hold a

value from 0 to 255.

***/

int val = analogRead(0) / 4;

/***

Update the particular EEPROM cell.

these values will remain there when the board is

turned off.

***/

EEPROM.update(address, val);

/***

The function EEPROM.update(address, val) is equivalent to the following:

if( EEPROM.read(address) != val ){

EEPROM.write(address, val);

}

***/

/***

Advance to the next address, when at the end restart at the beginning.

Larger AVR processors have larger EEPROM sizes, E.g:

- Arduno Duemilanove: 512b EEPROM storage.

- Arduino Uno: 1kb EEPROM storage.

- Arduino Mega: 4kb EEPROM storage.

Rather than hard-coding the length, you should use the pre-provided length function.

This will make your code portable to all AVR processors.

***/

address = address + 1;

if (address == EEPROM.length()) {

address = 0;

}

/***

As the EEPROM sizes are powers of two, wrapping (preventing overflow) of an

EEPROM address is also doable by a bitwise and of the length - 1.

++address &= EEPROM.length() - 1;

***/

delay(100);

}

The sketch is written to accept input from analog pin A0, which is where we connected our potentiometer. It takes the input and divides it by four so that it is in the range of 0 – 255, which can be represented by a single byte.

That value is then written to the first EEPROM address, but only if the data is different than the current data. Obviously, the first time you run it it will always perform a write operation, but during subsequent runnings, it will only write if the value is different than the current one.

Load the sketch from the examples and send it to your Arduino. Then turn the potentiometer and the data will be recorded to the EEPROM.

Now that we have some data, let’s read it back.

EEPROM Read

From its name, I believe you can guess what this sketch does!

EEPROM Read

/*

* EEPROM Read

*

* Reads the value of each byte of the EEPROM and prints it

* to the computer.

* This example code is in the public domain.

*/

#include <EEPROM.h>

// start reading from the first byte (address 0) of the EEPROM

int address = 0;

byte value;

void setup() {

// initialize serial and wait for port to open:

Serial.begin(9600);

while (!Serial) {

; // wait for serial port to connect. Needed for native USB port only

}

}

void loop() {

// read a byte from the current address of the EEPROM

value = EEPROM.read(address);

Serial.print(address);

Serial.print("\t");

Serial.print(value, DEC);

Serial.println();

/***

Advance to the next address, when at the end restart at the beginning.

Larger AVR processors have larger EEPROM sizes, E.g:

- Arduno Duemilanove: 512b EEPROM storage.

- Arduino Uno: 1kb EEPROM storage.

- Arduino Mega: 4kb EEPROM storage.

Rather than hard-coding the length, you should use the pre-provided length function.

This will make your code portable to all AVR processors.

***/

address = address + 1;

if (address == EEPROM.length()) {

address = 0;

}

/***

As the EEPROM sizes are powers of two, wrapping (preventing overflow) of an

EEPROM address is also doable by a bitwise and of the length - 1.

++address &= EEPROM.length() - 1;

***/

delay(500);

}

The sketch simply reads the EEPROM and prints the data to the serial monitor. So if you were to run it after the previous sketch you should see the values created by the potentiometer movements.

The sketch uses a tab character (“\t”) to format the display nicely, show you both the address and data value of each EEPROM location.

EEPROM Clear

The EEPROM Clear sketch resets all of the values in the EEPROM to zero.

EEPROM Clear

/*

* EEPROM Clear

*

* Sets all of the bytes of the EEPROM to 0.

* Please see eeprom_iteration for a more in depth

* look at how to traverse the EEPROM.

*

* This example code is in the public domain.

*/

#include <EEPROM.h>

void setup() {

// initialize the LED pin as an output.

pinMode(13, OUTPUT);

/***

Iterate through each byte of the EEPROM storage.

Larger AVR processors have larger EEPROM sizes, E.g:

- Arduno Duemilanove: 512b EEPROM storage.

- Arduino Uno: 1kb EEPROM storage.

- Arduino Mega: 4kb EEPROM storage.

Rather than hard-coding the length, you should use the pre-provided length function.

This will make your code portable to all AVR processors.

***/

for (int i = 0 ; i < EEPROM.length() ; i++) {

EEPROM.write(i, 0);

}

// turn the LED on when we're done

digitalWrite(13, HIGH);

}

void loop() {

/** Empty loop. **/

}

The sketch works by using the Write method to go through the entire EEPROM and set each value to zero.

Try running this sketch after you read the EEPROM values with the previous sketch. Then go back and reread the values using the EEPROM Read sketch again. You should find them they are now all zeros.

This is a quick way of clearing an EEPROM, however as it writes to every location it also consumes one of the limited write operations, So only run it when you really need to.

The three previous examples show you just how easy it is to work with the Arduino internal EEPROM using the EEPROM library. You can also experiment with the other examples as well.

Using External EEPROM

If the limited amount of nonvolatile storage in the Arduino is insufficient for your application then you can add an external EEPROM. Using an I2C device simplifies both the wiring and code.

AT24LC256 EEPROM

The AT24LC256 is a 256 Kilobit EEPROM. As there are eight bits in a byte this translates to 32 Kb of nonvolatile memory.

This I2C EEPROM has three I2C address lines, allowing you to select from one of eight possible addresses. So you can add more AT24LC256 chips to your design if you need more storage space.

The device, which is also branded “AT24C256” (the “L” is for the popular low-powered version of the chip), is capable of over 1 million write cycles, so it is more robust than the EEPROM included in the Arduino.

The device is available in several packages, including a 8-pin DIP. The pinouts of the chip are as follows:

- A0-A2 (pins 1-3) – These pins determine the I2C address of the chip.

- WP (pin 7) – This is Write Protect. Bringing this pin HIGH will prevent the EEPROM from being written to.

- SDA (pin 5) – Thi is the Serial Data for the I2C connection.

- SCL (pin 6) – This is the Serial Clock for the I2C connection.

There is also a VCC (pin 8) and GND (pin 4) connection for power and ground respectively.

AT24LC256 Modules

You can purchase the AT24LC256 in an 8-pin DIP, which is the best choice if you are developing a project using a circuit board. But for breadboarding there is another option.

The EEPROM is also available in several handy breakout modules, making it even easier to experiment with. These modules have the AT24LC256 chip, jumpers (or a DIP switch) for setting the I2C address and four connections for the I2C bus. Some modules also incorporate the pullup resistors required on the I2C line.

In my experiments I’ll be using a module as it’s easier to work with, however you can certainly substitute the actual chip if you wish.

External EEPROM Hookup

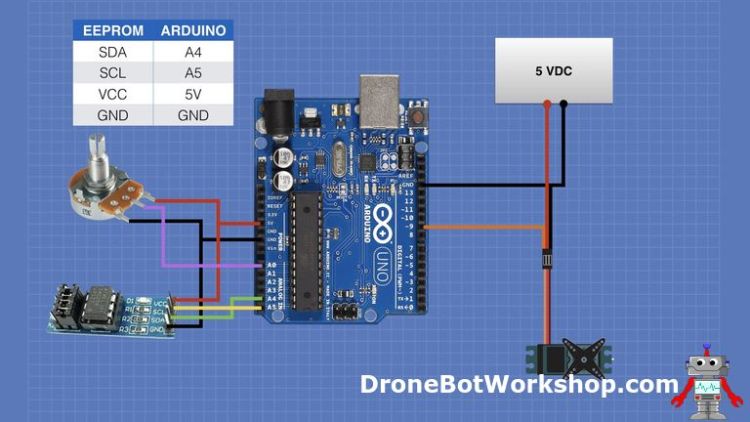

Our experiment will make use of an Arduino Uno, an AT24LC256 EEPROM module, a potentiometer, and a small servo motor. I used a 10K linear-taper potentiometer, but any value from 5K upwards will work fine. The servo I used was a common SG90 plastic servo.

Note that on the hookup I used a seperate 5-volt power supply for the servo motor, I prefer this over using the 5-volts from the Arduino as it avoids the possibility of inducing electrical noise into the Arduino’s power supply lines. However, you can use the Arduino 5-volt supply if you wish, it might be a good idea to put a small electrolytic capacitor across the supply line to absorb any noise.

You can also use an AT24LC256 8-pin DIP instead of a module, if you do you’ll probably need to add a couple of pullup resistors to the SDA and SCL lines.

Regardless of whether you use a module of just a chip you will want to ground all of the I2C address lines, setting up an address of 50 Hexadecimal. You’ll also want to ground the WP (write protect) pin so that you can write to the EEPROM.

External EEPROM Arduino Code

Now that we have everything hooked up let’s look at the code.

Our sketch will record the servo movements in the EEPROM. It will do that for about a minute and then end (you can make it longer if you wish). After that, it will wait five seconds and then playback the movements. The serial monitor will display both the recording and playback.

External EEPROM Demo

/*

External EEPROM Recording & Playback Demo

ext_eeprom_demo.ino

Uses AT24LC256 External I2C EEPROM

DroneBot Workshop 2019

https://dronebotworkshop.com

*/

// Include the I2C Wire Library

#include "Wire.h"

// Include the Servo Library

#include "Servo.h"

// EEPROM I2C Address

#define EEPROM_I2C_ADDRESS 0x50

// Analog pin for potentiometer

int analogPin = 0;

// Integer to hold potentiometer value

int val = 0;

// Byte to hold data read from EEPROM

int readVal = 0;

// Integer to hold number of addresses to fill

int maxaddress = 1500;

// Create a Servo object

Servo myservo;

// Function to write to EEPROOM

void writeEEPROM(int address, byte val, int i2c_address)

{

// Begin transmission to I2C EEPROM

Wire.beginTransmission(i2c_address);

// Send memory address as two 8-bit bytes

Wire.write((int)(address >> 8)); // MSB

Wire.write((int)(address & 0xFF)); // LSB

// Send data to be stored

Wire.write(val);

// End the transmission

Wire.endTransmission();

// Add 5ms delay for EEPROM

delay(5);

}

// Function to read from EEPROM

byte readEEPROM(int address, int i2c_address)

{

// Define byte for received data

byte rcvData = 0xFF;

// Begin transmission to I2C EEPROM

Wire.beginTransmission(i2c_address);

// Send memory address as two 8-bit bytes

Wire.write((int)(address >> 8)); // MSB

Wire.write((int)(address & 0xFF)); // LSB

// End the transmission

Wire.endTransmission();

// Request one byte of data at current memory address

Wire.requestFrom(i2c_address, 1);

// Read the data and assign to variable

rcvData = Wire.read();

// Return the data as function output

return rcvData;

}

void setup()

{

// Connect to I2C bus as master

Wire.begin();

// Setup Serial Monitor

Serial.begin(9600);

// Attach servo on pin 9 to the servo object

myservo.attach(9);

// Print to Serial Monitor

Serial.println("Start Recording...");

// Run until maximum address is reached

for (int address = 0; address <= maxaddress; address++) {

// Read pot and map to range of 0-180 for servo

val = map(analogRead(analogPin), 0, 1023, 0, 180);

// Write to the servo

// Delay to allow servo to settle in position

myservo.write(val);

delay(15);

// Record the position in the external EEPROM

writeEEPROM(address, val, EEPROM_I2C_ADDRESS);

// Print to Serial Monitor

Serial.print("ADDR = ");

Serial.print(address);

Serial.print("\t");

Serial.println(val);

}

// Print to Serial Monitor

Serial.println("Recording Finished!");

// Delay 5 Seconds

delay(5000);

// Print to Serial Monitor

Serial.println("Begin Playback...");

// Run until maximum address is reached

for (int address = 0; address <= maxaddress; address++) {

// Read value from EEPROM

readVal = readEEPROM(address, EEPROM_I2C_ADDRESS);

// Write to the servo

// Delay to allow servo to settle in position

// Convert value to integer for servo

myservo.write(readVal);

delay(15);

// Print to Serial Monitor

Serial.print("ADDR = ");

Serial.print(address);

Serial.print("\t");

Serial.println(readVal);

}

// Print to Serial Monitor

Serial.println("Playback Finished!");

}

void loop()

{

// Nothing in loop

}

Unlike the internal EEPROM, we are not going to use a special library to work with the AT24LC256. We will, however, be using the Arduino Wire library for I2C, as well as the Servo Library. Both of these libraries are already included in your Arduino IDE.

After including the required libraries we set up a few constants and variables.

- EEPROM_I2C_ADDRESS – A constant representing the EEPROM I2C address, in our case it is 50 Hexadecimal.

- analogPin – The pin connected to the potentiometer wiper, in this case A0.

- val – An integer used to represent the value sent to the servo motor during recording.

- readVal – An integer used to represent the value sent to the servo motor during playback.

- maxaddress – The highest address location we want to use. If you wish you can increase this, I used 1500 to minimize the time it took to run the demo.

We then create a servo object called myservo to represent the motor.

Next, we define two functions, writeEEPROM and readEEPROM, which perform our EEPROM writing and reading respectively.

The writeEEPROM function takes the memory address, the data you wish to write to that address and the EEPROM I2C address as inputs. It then connects to the EEPROM and passes the memory address as two independent bytes. This is because the I2C bus only allows you to transfer one address byte at a time.

Next, we place the value we wish to record onto the I2C bus. After that, we end the transmission.

I’ve also added a 5ms delay after writing, as the EEPROM requires this between writes.

The readEEPROM function takes the memory address and I2C address as inputs. It then connects to the I2C bus, passes the address information and ends the transmission. This causes the EEPROM to place the data at the specified address into its output buffer, ready to be read by the host. We read that value and then output it to end the function.

The setup is where we put everything together.

We start by connecting to the I2C bus as master, setting up the serial monitor and attaching to the servo motor on pin 9.

After printing to the serial monitor we go into a for-next loop, cycling through all of the addresses. On each address we capture the value from the analog port that the potentiometer is attached to and convert it to a value from 0-180 for our servo motor.

We write to the servo and allow a 15ms delay for it to settle into position. Then we write the value to the EEPROM and print it to the serial monitor.

After cycling through the addresses we print to the serial monitor again and wait five seconds.

Then we run through the addresses again. This time we read every value and write it to both the serial monitor and servo motor. Once again we provide a delay for the servo.

Finally, we print to the serial monitor and end the setup.

As all of the “action” takes place in the Setup routine there is nothing to do in the loop.

Running the External EEPROM Sketch

Load the sketch to your Arduino and start turning the potentiometer. You should observe the servo turning accordingly, as well as the data being displayed on the serial monitor.

After about a minute the recording will end. Following a 5-second delay, the motor will start moving on its own, in the same pattern you recorded.

You could make many modifications to this code and even use is at the basis as a recorder and playback unit with the addition of a couple of pushbuttons and perhaps a few status LEDs.

Or, as a simple experiment, try removing the section of code that does the recording after you run it the first time. Then run the sketch again, using only the playback features. You should observe the motor turning in the same pattern. You could then power everything down and power up the Arduino again, the non-volatile EEPROM memory will put the servo through its paces as it did before.

Conclusion

Having some non-volatile memory in your Arduino project can really add a new dimension. If you only need to store a few parameters you can make use of the Arduinos internal EEPROM. And for large memory requirements, you can use external EEPROM.

Just remember the limitations of EEPROM, don’t write to it too often and you’ll soon have an Arduino that is like an elephant – it never forgets!

Resources

Code for this Article – All the code used in this article in a handy ZIP file.

PDF Version – A PDF version of this article, great for printing and using on your workbench.

I2C EEPROM – Article and code on Arduino Playground

'사물인터넷' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Stepper Motor with Hall Effect Limit & Homing Switches (0) | 2021.07.04 |

|---|---|

| I2C Between Arduino & Raspberry Pi (0) | 2021.07.04 |

| Analog Feedback Servo Motor (0) | 2021.07.04 |

| Arduino High-Current Interfacing – Transistors & MOSFETs (0) | 2021.07.04 |

| TB6612FNG H-Bridge with Arduino – Better Than L298N? (0) | 2021.07.04 |