출처: https://dronebotworkshop.com/transistors-mosfets/

Arduino High-Current Interfacing - Transistors & MOSFETs

Learn how to use Bipolar Junction Transistors and MOSFETs to interface high-current DC loads with an Arduino.

dronebotworkshop.com

Arduino’s are excellent microcontrollers but they can only control low-current devices. There are several ways to extend the capability of your Arduino to allow it to drive higher current loads. Today we will look at a couple of them.

Follow along as we learn to use transistors and MOSFETs with our Arduino.

Introduction

The Arduino is a microcontroller, you probably already know that. The very name “microcontroller” tells us that the primary purpose of this device s to control things. The “micro” part simply means that it is a very tiny device.

The Arduino, or any microcontroller, is tiny in more than just size. It also has a pretty small current capability, limiting its use to directly controlling only small devices such as single LEDs, OLEDs, and LCD displays.

Of course, that hasn’t stopped us from controlling much larger devices like gear motors and large stepper motors. We accomplished this by using a driver board to take the low-current Arduino control signals and drive the high-current motors. In these cases, the driver board did all of the heavy lifting for us.

The driver boards we have been using accomplish their magic using devices like transistors and MOSFETs. These are basic electronic components that are used in a myriad of applications, in fact, the Arduino itself is a collection of transistors on a single chip.

Today we will learn to use these components to extend the current-driving capability of our Arduino designs.

Transistors and MOSFETS

In 1947 American physicists John Bardeen and Walter Brattain, working under physicist William Shockley at Bell Labs in Murray Hill, New Jersey, invented the first point-contact transistor. A year later Shockley invented and patented the first bipolar transistor.

This work resulted in all three men earning the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics for their research on semiconductors and their discovery of the transistor effect. And their invention literally changed the world.

Transistors are the basis of virtually every electronic device created today. The powerful desktop computers and compact smartphones we know and love owe their existence to tiny transistors etched onto silicon chips. Advances in medicine, space research and even the Internet itself would not have occurred without the transistor.

Transistors replaced vacuum tubes and they could act as either amplifiers or electronic switches. We will be making use of the latter capability.

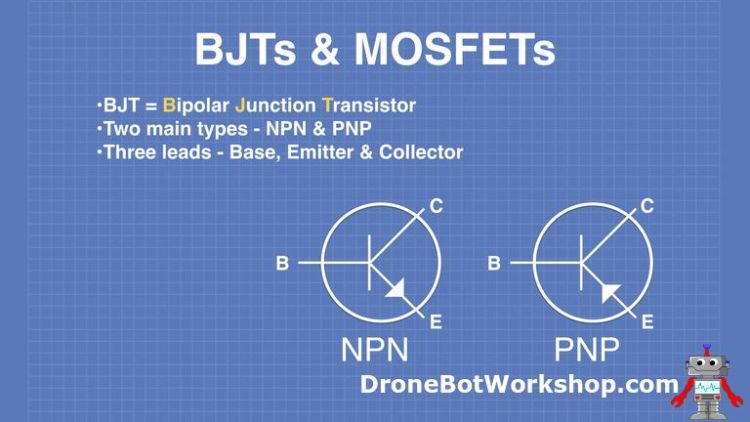

Bipolar Junction Transistors (BJTs)

The “standard” transistor is the Bipolar Junction Transistor, or BJT. These are sometimes just called Bipolar Transistors.

A BJT has three leads:

- Base

- Emitter

- Collector

There are two types of BJTs – NPN and PNP.

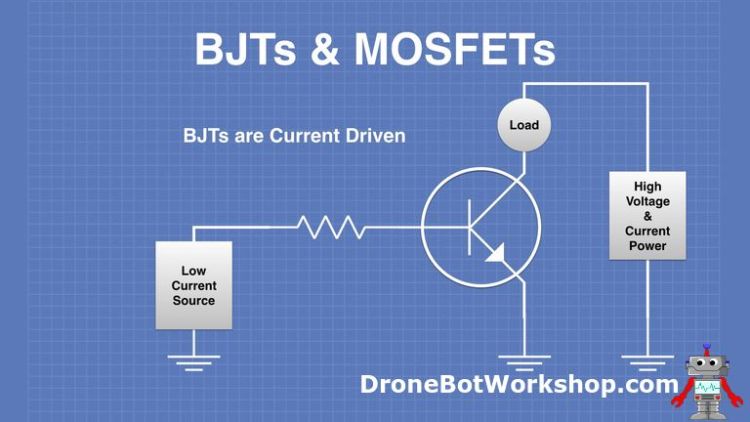

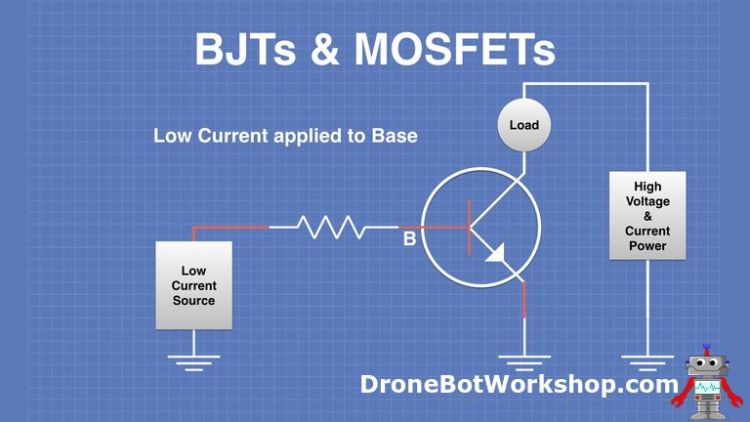

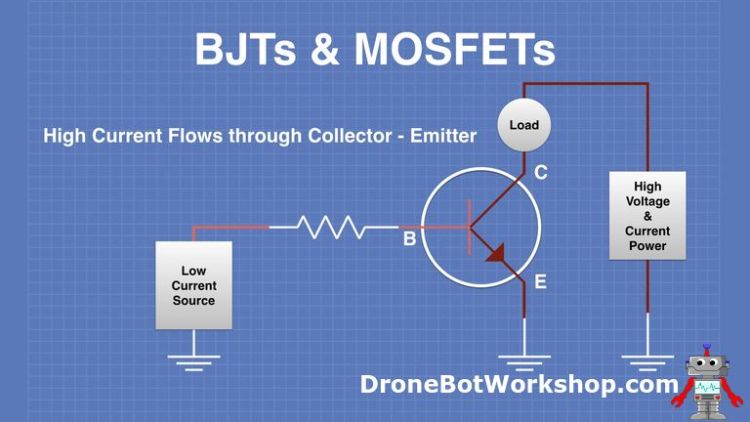

A BJT is current driven, that is to say that it is switched on when current flows between the base and emitter.

A sufficient current flowing into the base will switch on the transistor and allow current to flow between the emitter and collector.

When the BJT is switched on it behaves a lot like a diode. In a way you can think of it as a switchable diode.

MOSFETs

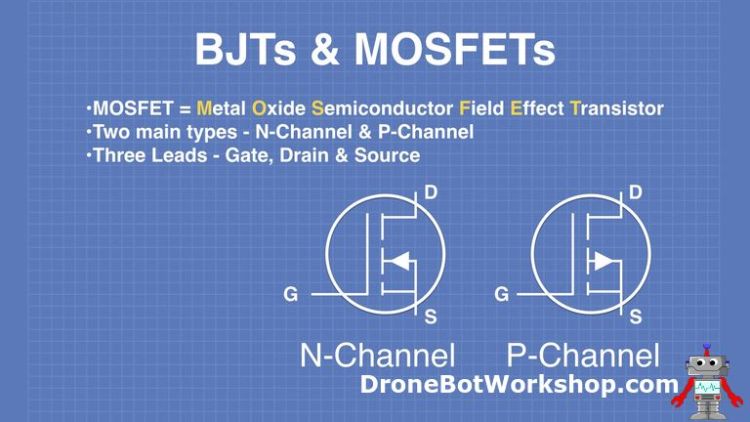

The Metal Oxide Semiconductor Field Effect Transistor, or MOSFET, is an improvement on the BJT in many ways. It is a high impedance device that uses a low voltage to switch it on.

As with a BJT a MOSFET has three leads.

- Gate

- Drain

- Source

There are two types of MOSFETs, N-Channel and P-Channel.

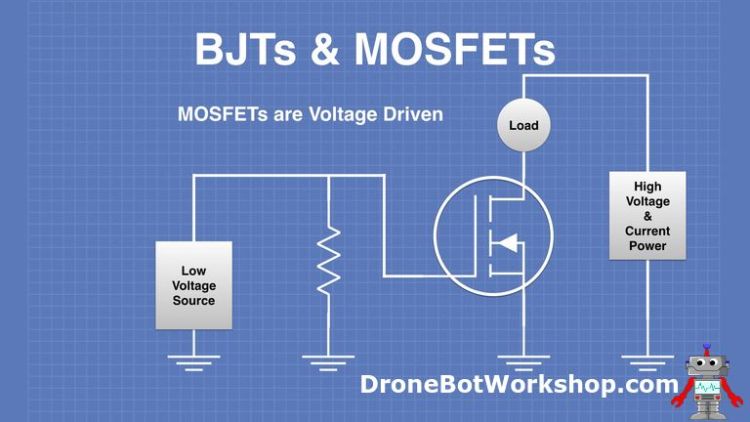

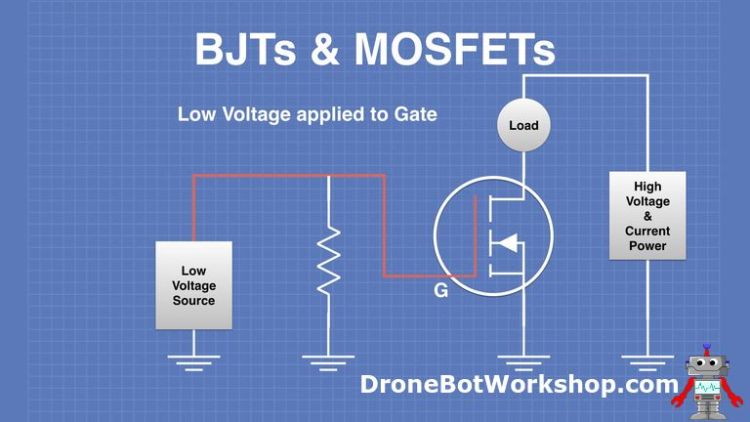

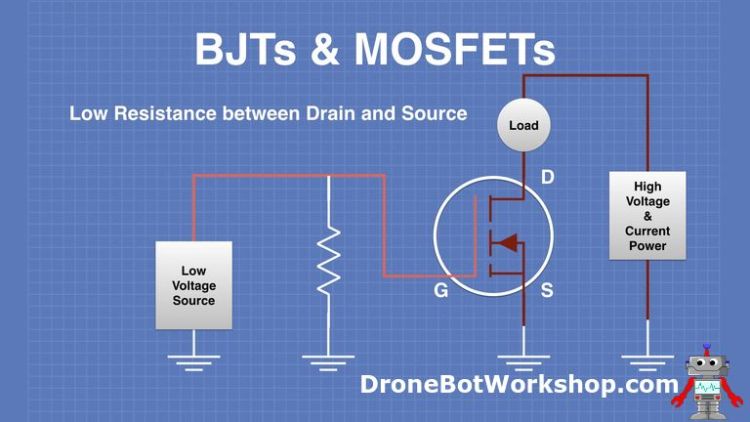

This diagram illustrates a MOSFET in a circuit with a low voltage source connected to the Gate.

When a sufficient voltage is applied to the gate the MOSFET is switched on.

This allows current to flow between the Drain and the Source. The MOSFET acts like a very low value resistor when it is switched on.

Since MOSFETs have a very low on resistance they don’t dissipate very much power, so they stay cool even without heatsinks.

BJTs vs. MOSFETs

So which of the two types of transistors would be best for your design?

The answer is not always straightforward as both Bipolar Junction Transistors (BJTs) and MOSFETs have their own strengths and weaknesses.

This chart outlines some of those differences:

| BJT | MOSFET |

| Current Controlled. Requires biasing current and limiting resistor. | Voltage Controlled. No biasing current or limiting resistor. |

| Lower impedance. Draws more current. | Higher impedance. Draws minimal current. |

| Higher gain than MOSFETs. | Lower gain than BJT’s. |

| Larger internal size than MOSFETs. | Smaller internal size than BJTs. |

| Less expensive than MOSFETs. | More expensive than BJTs |

As you can see in most applications the MOSFET has some distinct advantages over the BJT. But in some cases, such as in the design of amplifiers, or where cost is a factor, bipolar junction transistors can be a better choice.

Our Transistor & MOSFET

Here are the devices we will be using in our ex[periments. Both of them are very common devices that your local electronics store will have in stock. You can substitute other devices with similar specifications.

TIP120 Darlington Transistor

The TIP120 is an NPN Darlington Power Transistor. It can switch loads up to 60-volts with a peak current of 8 amperes and a continuous current of 5 amperes.

A Darlington transistor consists of a pair of transistors in the same package. The emitter of the first transistor is connected with the base of the second transistor and the collectors of both transistors are connected together to form a Darlington pair.

This arrangement improves both the current gain and current rating of the transistor.

Here are the main specifications of the TIP120:

- NPN Medium-power Darlington Transistor

- High DC Current Gain (hFE), typically 1000

- Continuous Collector current (IC) is 5A

- Collector-Emitter voltage (VCE) is 60V

- Collector-Base voltage (VCB) is 60V

- Emitter Base Voltage (VBE) is 5V

- Base Current(IB) is 120mA

- Peak load current is 8A

- Available in To-220 Package

IRF520 MOSFET

The IRF520 is a Power Mosfet with a 9.2-ampere collector current and 100-volt breakdown voltage. This MOSFET has a low gate threshold voltage of 4 volts and hence is commonly used with microcontrollers like the Arduino for switching high current loads.

Here are the main specifications of the IRF520:

- N-Channel Power MOSFET

- Continuous Drain Current (ID): 9.2A

- Drain to Source Breakdown Voltage: 100V

- Drain Source Resistance (RDS) is 0.27 Ohms

- Gate threshold voltage (VGS-th) is 4V (max)

- Rise time and fall time is 30nS and 20nS

- It is commonly used with Arduino, due to its low threshold voltage.

- Available in To-220 package

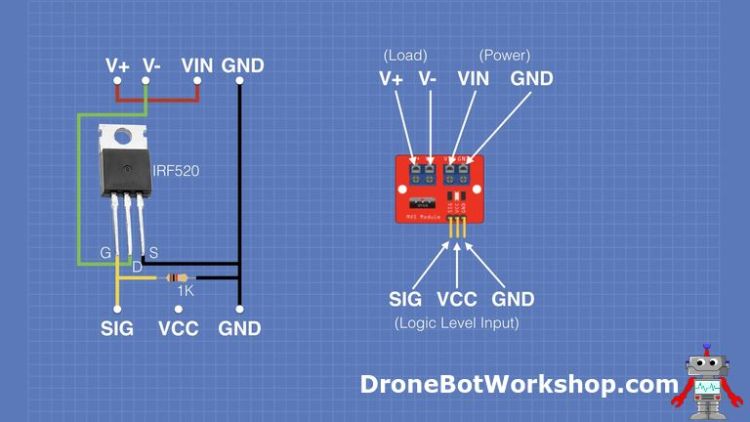

Popular MOSFET Module

One reason that I chose to use the IRF520 for my MOSFET experiments is that it is available as a low-cost module. The module has a few supporting components, as well as screw terminals for power and the load you are controlling. It also has a 3-pin connector for connecting to the Arduino or other microcontrollers.

I’ll be using these modules in my MOSFET example, but you could always elect to use discrete IRF520s instead. I’ll show you both ways in the wiring diagram.

Arduino with Transistors

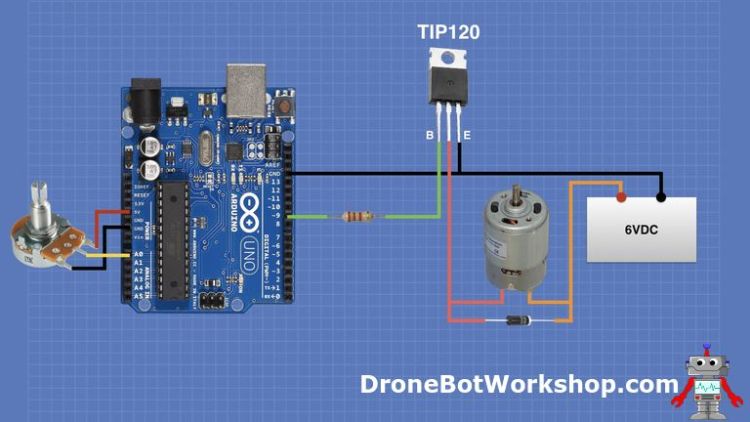

For the first couple of experiments, we will use the TIP120 power Darlington BJT. You can substitute a BJT with similar specifications if you don’t have a TIP120.

I’ll be using 6-volt batteries and loads for my experiments, but you can use any DC power source and load up to 40 volts. Don’t try and switch AC voltage using the methods you’re about to see, these are strictly DC circuits.

Basic Arduino Transistor Switch

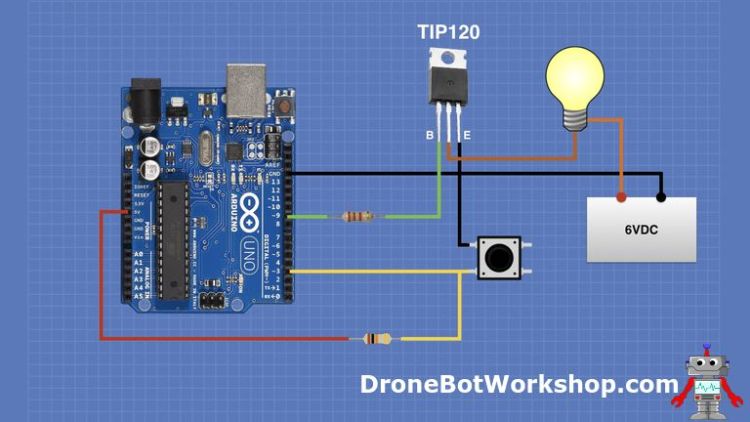

The first experiment is the basic switch. It’s a simple hookup and sketch and it illustrates how simple it is to control a load with a transistor and an Arduino.

For my high-current load, I’m using a 6-volt incandescent light bulb. You could select another resistive load if you wish.

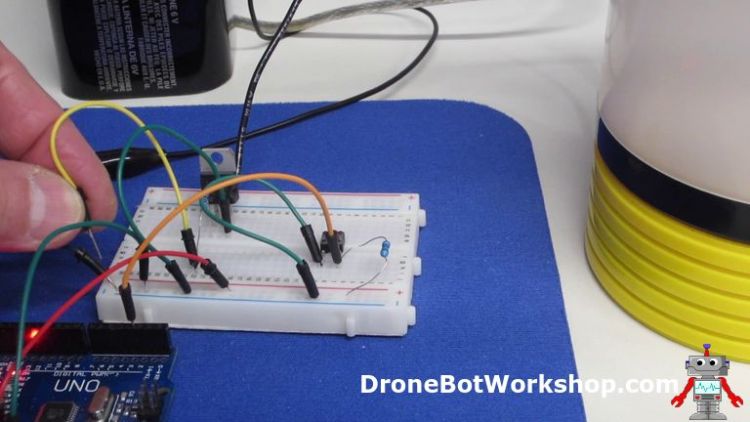

Here is how I hooked everything up:

Note that in addition to the Arduino, TIP120, light bulb and battery you’ll need a pushbutton switch and a couple of resistors. The 2.2k resistor limits the current into the base of the transistor, while the 10k resistor is a pull-up resistor for the switch.

Hook everything up and then load the following sketch:

/*

Transistor Switch Demonstration

transistor-switch-demo.ino

Demonstrates use of BJT to switch 6-volt incandescent lamp

Uses pushbutton for input

DroneBot Workshop 2019

https://dronebotworkshop.com

*/

// Output pin to transistor base

int outPin = 9;

// Input pin from pushbutton

int buttonPin = 3;

// Pushbutton value

int buttonVal;

void setup()

{

// Setup transistor pin as output

pinMode(outPin, OUTPUT);

// Setup pushbutton pin as input

pinMode(buttonPin, INPUT);

// Make sure transistor is off

digitalWrite(outPin, LOW);

}

void loop()

{

//Read pushbutton input

buttonVal = digitalRead(buttonPin);

//Check button position

if (buttonVal == HIGH) {

// Button is not pressed, turn off lamp

digitalWrite(outPin, LOW);

delay(20);

} else {

// Button is pressed, turn on lamp for 5 seconds

digitalWrite(outPin, HIGH);

delay(5000);

digitalWrite(outPin, LOW);

}

}

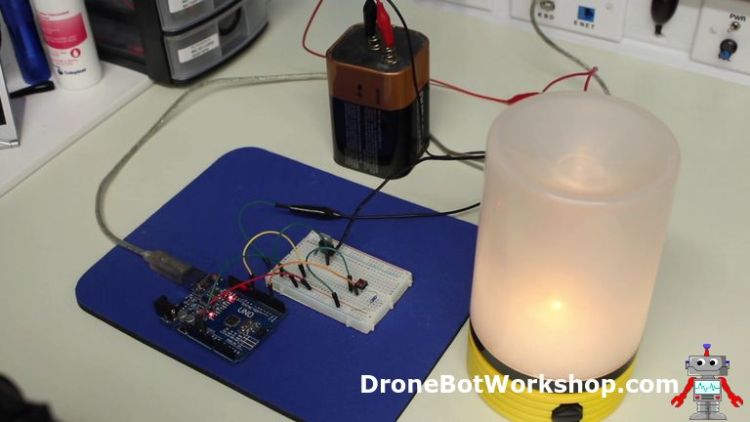

The sketch for our switching experiment is pretty simple. Its purpose is to light the bulb for 5-seconds when the pushbutton is pressed.

We start by defining variables to represent the output pin to the transistor and the input pin from the switch. We also define a variable to hold the pushbutton value.

In the Setup, we set our inputs and outputs, and then write a LOW to the output pin to make sure we enter the loop with the transistor off.

In the Loop, we read the input pin and use its value for the button value. If it is HIGH then the button has not been pressed and the 10k resistor is pulling the input up to 5-volts.

If the button is pressed the input will go to ground and the value will be LOW. We turn on the lamp by setting the output HIGH, which passes current through the 2.2k resistor to the transistor base.

We want our light to stay on for a while so we add a 5-second delay. We then set the output LOW to turn off the lamp and go back and finish the loop.

Load the sketch and observe the results. You can increase or decrease the delay if you wish.

Switching Inductive Loads

The arrangement we just saw with the transistor and the Arduino works well for resistive loads, but for inductive loads, there is another consideration.

What is an inductive load you might ask?

An inductive load refers to any load that passes electricity through a coil. Examples would be motors, relays, and solenoids.

When current is passed through a coil it creates a magnetic field and a small current is generated in the opposite direction. This is sometimes called “reverse EMF” or “backflow voltage”.

A device like a motor or a solenoid can have a large reverse EMF when it is in movement. That reverse voltage can damage transistors, so they need to be protected from it.

The most common method of protecting from reverse EMF damage is to use a diode, wired in the “opposite” polarity. This absorbs the reverse voltage.

In our experiment, we will use an inductive load in the form of a small DC motor.

Note the diode across the motor leads, I used an IN4004 rectifier diode, which is a very common device.

The rest of the wiring is pretty straightforward. Once again I’m using a 6-volt battery to power the experiments high-current side, and we’re using a 2.2k resistor to limit the current into the transistor base.

We have also added a potentiometer so that we can control the motor speed.

Here is the sketch we’ll be using for the motor control:

/*

Transistor Inductive Control Demonstration

transistor-induct-control-demo.ino

Demonstrates use of BJT to control a 6-volt DC motor

Uses potentiometer for input

DroneBot Workshop 2019

https://dronebotworkshop.com

*/

// Output pin to transistor base

int outPin = 9;

// Input from potentiometer

int potIn = A0;

// Variable to hold speed value

int speedVal;

void setup()

{

// Setup transistor pin as output

pinMode(outPin, OUTPUT);

}

void loop()

{

// Read values from potentiometer

speedVal = analogRead(potIn);

// Map value to range of 0-255

speedVal = map(speedVal, 0, 1023, 0, 255);

// Write PWM to transistor

analogWrite(outPin, speedVal);

delay(20);

}This is also a simple sketch, it’s purpose is to read the potentiometer position and set the motor speed accordingly.

We start by defining our output to the transistor and the analog input pin used by the potentiometer. We also define a variable t hold the motor speed,

All we do in the Setup is to define our transistor connection as an output.

In the Loop, we read the potentiometer position and then use the map command to convert it into a range of 0-255. We then use an analogWrite command to send PWM signals out to our transistor. This switches the transistor on and off, powering our motor.

Load the sketch and experiment with controlling the motor speed. Because we are using PWM the motor should have good torque even at the slower speeds.

If you need to control the speed of a small DC motor and don’t need to reverse it then this is actually a practical circuit. Just remember that you’ll be losing 0.7 of a volt through the transistor.

Arduino with MOSFETs

MOSFETs have a number of advantages over BJTs. They cost more, but for that extra money, you get much better power dissipation and simplicity in hooking them up to your logic circuits.

We will be making use of the IRF520 N-Channel Power MOSFET for our experiments. I’m going to be using a popular “MOSFET Module” that simplifies hooking up external devices to your microcontroller, but you may also just use discrete MOSFETs instead.

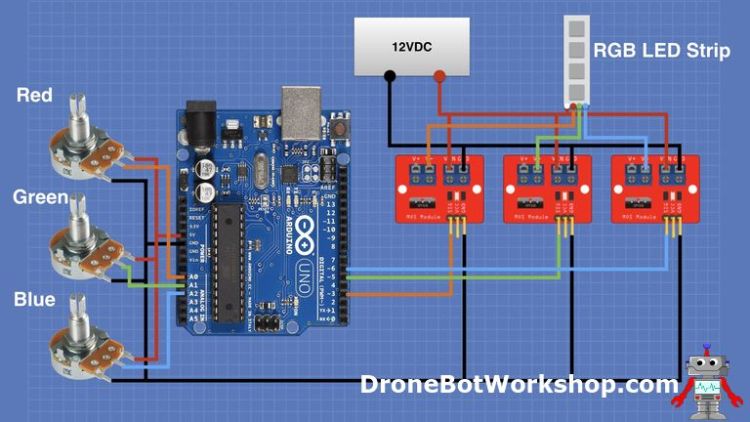

Arduino MOSFET RGB LED Strip Driver

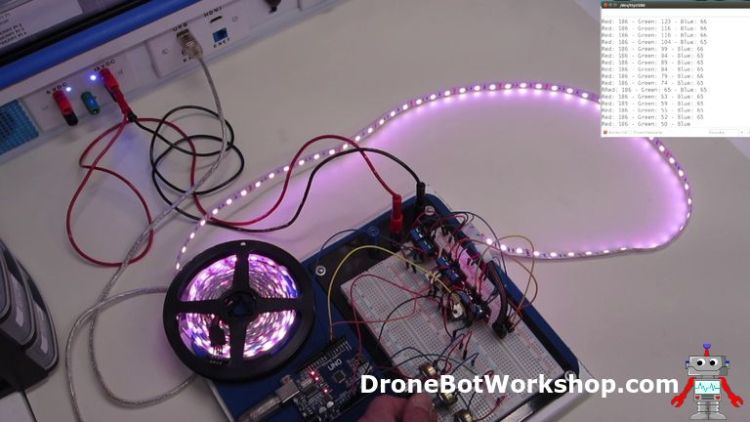

Our experiment will involve using an Arduino to control a 5-meter strip of RGB LED strip lights. We’ll have three potentiometers to control the intensity of all three colors, allowing us to dial-up a rainbow of colors.

You’ll require three MOSFETs or MOSFET Modules to wire this up, as well as a 12-volt power supply with enough current to power the LED strip, which can consume several amperes.

I used the MOSFET Modules in my design, but if you want to use discrete MOSFETs instead you can use this diagram to equate the two.

Notice that the VCC pin on the module is not connected to anything. Also, the Vin and V+ pins are just tied together.

The diagram does not show an additional 1k resistor and an LED that the module uses to display activity on the MOSFET gate input.

Here is the wiring diagram.

In retrospect, you don’t need the connections from the power supply positive to the module V+, they don’t actually go anywhere. Only the connection to the LED strip positive common is required.

The hookup is pretty straightforward, essentially we are connection the three potentiometers to three analog inputs and the three MOSFET modules to output pins that are capable of PWM. The LED strip lights are connected to the power supply through the MOSFET outputs.

Here is the sketch we will be using to make all of this work:

/*

MOSFET RGB LED Strip Demonstration

mosfet-rgb-led-demo.ino

Demonstrates use of MOSFETs to drive RGB LED Strip

Uses three potentiometers for input

DroneBot Workshop 2019

https://dronebotworkshop.com

*/

// Output pins to MOSFETs

int redPin = 3;

int greenPin = 5;

int bluePin = 6;

// Define Potentiometer Inputs

int redControl = A0;

int greenControl = A1;

int blueControl = A2;

// Variables for Values

int redVal;

int greenVal;

int blueVal;

void setup()

{

// Setup MOSFET pins as outputs

pinMode(redPin, OUTPUT);

pinMode(greenPin, OUTPUT);

pinMode(bluePin, OUTPUT);

// Setup Serial Monitor

Serial.begin(9600);

}

void loop() {

// Read values from potentiometers

redVal = analogRead(redControl);

greenVal = analogRead(greenControl);

blueVal = analogRead(blueControl);

// Map values to range of 0-255

redVal = map(redVal, 0, 1023, 0, 255);

greenVal = map(greenVal, 0, 1023, 0, 255);

blueVal = map(blueVal, 0, 1023, 0, 255);

// Write PWM to pins

analogWrite(redPin, redVal);

analogWrite(greenPin, greenVal);

analogWrite(bluePin, blueVal);

// Write Color values to Serial Monitor

Serial.print("Red: ");

Serial.print(redVal);

Serial.print(" - Green: ");

Serial.print(greenVal);

Serial.print(" - Blue: ");

Serial.println(blueVal);

// Add a slight delay

delay(20);

}Another simple sketch, actually it’s very similar to the one we used to control the motor with a BJT.

We define the pins we’ll be using for the outputs to the MOSFETs, and the analog pins used by the three potentiometers. We also define three variables to hold the three color values.

In the Setup, we set the pins connected to the MOSFETs as outputs. We also set up the serial monitor, this is optional and is included for troubleshooting purposes only.

In the Loop, we read the three potentiometers, convert their values to a range of 0-255 and then send PWM out to the three MOSFET switches to control our LEDs. It’s pretty straightforward.

Once you get everything hooked up give it a try. If you have trouble getting it to work look at the serial monitor to see what values you’re getting from the potentiometers.

It’s a colorful experiment!

Conclusion

By using BJTs and MOSFETs we can extend the control capability of our Arduino projects. We are no longer limited to devices under 40ma.

The techniques I showed you here can be used for a variety of DC loads, inductive and non-inductive. But they cannot be used to control AC devices, so don’t even try. There are other methods used to control AC devices, and we will look at them in a future article and video.

Until then you’ll have to limit yourself to controlling the DC equipment in your world. Have fun!

Resources

Code for this Article – All the code used in this article in a handy ZIP file.

PDF Version – A PDF version of this article, great for printing and using on your workbench.

Transistor Theory – An excellent tutorial from Sparkfun.

TIP120 – TIP120 Bipolar power transistor spec sheet.

IRF520 – IRF520 Power MOSFET spec sheet.

'사물인터넷' 카테고리의 다른 글

| EEPROM with Arduino – Internal & External (0) | 2021.07.04 |

|---|---|

| Analog Feedback Servo Motor (0) | 2021.07.04 |

| TB6612FNG H-Bridge with Arduino – Better Than L298N? (0) | 2021.07.04 |

| Color Sensing with Arduino (0) | 2021.07.04 |

| Measuring Temperature with Arduino (0) | 2021.07.04 |